History:

to ~1700 AD

With the arrival of the first Spanish colonists in the 1700s, grasslands experienced a dramatic shift in the type, intensity and timing of disturbance and a dramatic shift in species composition.

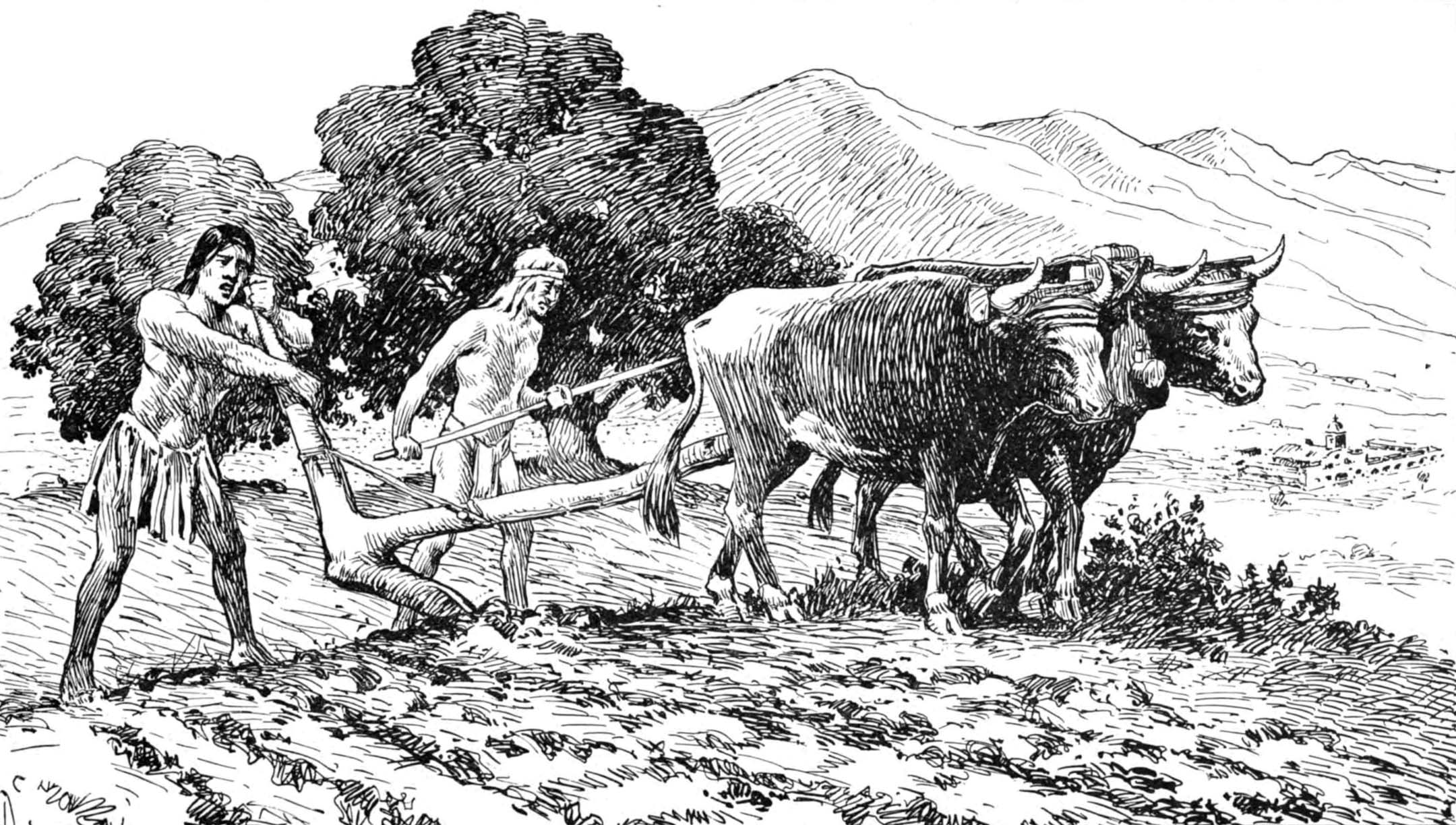

Introduction of Livestock

With the arrival of the first Spanish colonists in 1769 (Mission San Francisco de Asís in San Francisco was established 1776) in northern California new grazers entered California grasslands: domestic cattle, horses and sheep. The Russians at Fort Ross and Bodega (1812-1841) also brought livestock with them, but is wasn't until 1824 that livestock grazing became widespread with the establishment of Mexican land grants (Bartolome, et al. 2007).

Coastal prairies were considered prime property for cattle and sheep ranching because of their productive native perennial grasses (Burcham 1957: fort and Hayes 2007). Ranching was lucrative due to the increasing demand for beef. Human populations were burgeoning during the Gold Rush, and by 1880, there were 3 million cattle and 6 million sheep grazing California’s grasslands. By comparison, Barry et al (2006) estimate there are currently 2.9 million cattle and less than 500,000 sheep (Barry, Larson and George 2006)

With the spread of domestic grazers, invasive species also spread throughout grasslands, decreasing the quality of forage ( Burcham 1961). Exotic annuals may have taken the "upper hand" when native perennial grasses were severely overgrazed over several periods of extended drought (Howard 1998). Today, many of the local coastal ranching operations are beginning to retire, creating even greater threats to native coastal prairies.

Loss of Native Grazers

In more recent times, tule elk were a major contributor to grazing in coastal prairie. It is estimated that over 500,000 elk once roamed California. The Californios (California residents under the Spanish government centered in Mexico City) hunted elk for meat and for tallow, which was highly valued for cooking (Livingston 1995). Lieutenant Joseph Warren Revere (1812-1880), grandson of Paul Revere and an officer in the US Navy, Union Army and later the Mexican Army, describing his participation in an elk hunt at Point Reyes, writes that his party of Americans and Californio’s encountered a herd of over 400 “superb fat animals” (Revere 1849:81-87). The elk hunt occurred in August when the elk were “fatter than any other, and cannot compete with the horse in speed; whereas, a couple of months later, the fleetest horse could hardly overtake them” (Revere 1849).

Revere remarks on the “wholesale slaughter” of elk that he inferred from the bones and horns he observed strewn about the landscape from previous years hunts. Livingston (Livingston 1995) reports, “The beleaguered elk already were dwindling in numbers, and according to an account related by Rafael Garcia, the surviving herds swam across Tomales Bay to the wilderness of Sonoma County sometime in the late 1850’s or early 1860’s.” Rafael Garcia was a veteran of the Mexican army who owned the Rancho Tomales y Baulines.

Completely eliminated from Marin County by the 1860, the National Park Service in cooperation with the California Department of Fish & Game reintroduced eleven tule elk to Tomales Point In 1978. Two bulls and eight cows were brought to Point Reyes from San Luis Island Wildlife Refuge near Los Banos, California. By 1995, the population had grown to over 500 individuals (Dobrenz and Beetle 1966).The Point Reyes herd is now one of the largest populations in California with over 400 counted during the 2009 census (National Park Service 2009).

Introduction of Exotic Plants

The conversion of California’s grasslands to non-native grasslands began with European contact. European visitors and colonists introduced plants both intentionally and accidentally. Adobe bricks from the oldest portions of California’s missions (1791-1800s) contained remains of common barley (Hordeum vulgare), Italian ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum), redstem filaree (Erodium cicutarium), wild oat (Avena fatua), spiny sowthistle (Sonchus asper), curly dock (Rumex crispus), wild lettuce (Lactuca sp., wild mustard (Brassica sp.) and others (Hendry 1931).

Most of the nonnative and invasive plants in California originated from the Mediterranean region of Eurasia and North Africa. Exotic Mediterranean annual plants altered California’s native grasslands to such an extent that it has been called “the most spectacular biological invasion worldwide” (Kotanen 2004).

The arrival and introduction of exotic plant species with established populations that are considered naturalized in California can be divided into five periods of establishment and modes of entry (Bossard and Randall 2007):

- Spanish colonization era (1769-1825) when greater than 16 species introduced by the colonists and missionaries became naturalized in California.

- Mexican Period (1825-1848) when 63 alien plant species were introduced and naturalized due to trading networks between old Spanish settlements in Mexico and native California peoples.

- Gold Rush Period (1849-1860) when 55 plant species were arrived with imported supplies.

- Agricultural Diversification and Development Period (1860-1925) when 158 now naturalized plant species were introduced with the importation of agricultural supplies, domestic animals and seeds.

- Population Explosion Era (1925-2002) during which 654 species became naturalized in California due to continued accidental and purposeful introductions accompanying intense urbanization and suburbanization.

Plant Type Definitions

Types of plants in coastal prairies, as defined by Pysek, et al. 2004:

- Exotic, alien, introduced, non-native plants: plants that were intentionally or unintentionally transported by humans into an area in which they are not native. Also applies to plants that arrived without the help of people from an area in which they were also introduced.

- Naturalized plants: established alien plants that sustain self-replacing populations.

- Invasive plants: naturalized plants that spread or have the potential to spread over a large area.

- Casual alien plants or waifs: species escaped from cultivation and occur outside of cultivation.

- Weeds: native or non-native plants that grow in sites wehre they are not wanted and have negative economic or environmental impacts.

- Noxious: weeds whose control is considered mandatory by governing agencies.>

- Transformer: invasive native or non-native plants that cause substantial change to an area.

Annual plant invaders have had a more difficult time competing with the perennial grasses in coastal grasslands than in inland grasslands (Corbin and D'Antonio 2004). Perennial grasses in coastal prairies reduced the biomass of exotic annuals and over time decreased the areas in which exotic annual seeds could germinate. However, exotic annual grasses still have negative effects on native perennial grasses at all life stages resulting in reduced number of seeds produced, fewer seedlings that survive, reduced vigor of adult plants (Corbin, et al. 2007).

More recently, coastal prairies are being increasingly invaded by introduced perennials such as velvet grass (Holcus lanatus), tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), and Harding grass (Phalaris aquatica) (D'Antonio, et al. 2007). Many of these invasive perennial grasses were once recommended for forage and range improvement (Jones and Love 1945).

The Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus, introduced with barley perhaps 300 years ago may have been a major factor in the conversion of native grasslands to non-native grasslands (Borer, et al. 2007; Malmstrom, et al. 2005). The virus, spread by aphids, turns leaves yellow or bright red and is most damaging during drought conditions (Stromberg and Kephart n.d.). Plants infected with the virus produce far fewer healthy seeds than those not infected with the virus. Some plants, like wild oat (Avena spp.) may host the disease and spread the infection to surrounding plants.

Fire Suppression

Lightening and human-set fire plays an important role in the maintenance of grasslands and the structure of plant communities. Although coastal prairie grasslands may have been more difficult to burn in many areas as they remain green for much of the year, there is evidence that Indians regularly burned in coastal grasslands (Anderson 2005; Bicknell 1992; Bicknell, et al. 1993a; Bicknell, et al. 1993b; Bicknell, et al. 1993c; Dmytryshyn, et al. 1989; Kotzebue 1830; Lewis 1993; Marryat 1855).

According to Greenlee and Langenheim (1990), the Central Coast California has had five distinct fire regimes that had profound effects on the vegetation:

- Lightning (up to 11,000 years ago) Lightning ignited fires occur most often on mountain tops and forests (Greenlee and Langenheim). The lightning-set fire regime in California’s grasslands is estimated at from 1-15 years (USDA Forest Service 2005).

- Aboriginal (11,000 BP to 1792) Humans changed the lightening ignited regime when they arrived around 11,000 years ago by increasing the fire return interval in coastal grasslands. Native people set fires in grasslands to increase the quality and abundance of grassland plants they used for food and materials and to attract animals to the new growth. Native Americans increased the fire return interval to an average of every 2 years (USDA Forest Service 2005).

- Spanish (1792-1848) The Spanish prohibited Indian burning in grasslands to preserve the land for cattle grazing, but instead burned in chaparral and oak woodlands to increase the prairie for pasture lands. During that time a combination of fire suppression in grasslands, overgrazing, cultivation, and the introduction of annual grasses probably changed the fire behavior in prairies. Fire suppression began with the Spanish who prohibited Indian burning in grasslands because it interfered with the forage needs of their domestic cattle.

- Anglo (1847-1929) During the Anglo period, coastal grassland fires were suppressed to preserve forage for cattle. However, grassland fires in inland areas increased in both return interval and intensity since fires were purposely set in order to clear shrubland in favor of grassland (Kinney 1996).

- Recent (1929-1979) This era of fire suppression increased the fire return interval in prairies. Greenlee and Langenheim estimate the mean fire return interval in prairies in recent time is 20-30 years, up from 1-15 years during the lightening, aboriginal, and Spanish periods.

Further Reading

- Anderson MK. 2005. Tending the Wild. Berkeley CA: University of California Press. 526 p.

- Barry S, Larson S, George M. 2006. California Native Grasslands: A Historical Perspective. Grasslands, A Publication of the Native Grass Association XVI(5):7-11. 2012 Dec 12.

- Blackburn TC, Anderson K, editors. 1993. Before the Wilderness. Menlo Park CA: Ballena Press. 476 p.

- USDA Forest Service. 2005. Fire Regime Table. Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Accessed 2012 Dec 12.

- Greenlee, J. M., & Langenheim, J. H. (1990). Historic Fire Regimes and Their Relation to Vegetation Patterns in the Monterey Bay Area of California. The American Midland Naturalist, 124(2), 239–253.

- Goodrich J, Lawson C, Lawson VP. 1980. Kashaya Pomo Plants. Berkeley CA: Heyday Books.

- Kelly I. 1996. Interviews with Tom Smith and Maria Copa. Collier MET, Thalman SB, editors. San Rafael CA: Miwok Archeological Preserve of Marin. 543 p.

- Lewis HT. 1993. Patterns of Indian burning in California. In: Blackburn TC, Anderson MK, editors. Before the Wilderness. Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press. p 55-116.

- National Park Service. 2009. Viewing tule elk . Point Reyes National Seashore. National Park Service. Department of the Interior. Accessed 2012 Dec 12.

- Stewart OC. 2002. Forgotten Fires: Native Americans and the Transient Wilderness. Lewis HT, Anderson MK, editors. Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 364 p.

- Timbrook J. 1990. Ethnobotany of Chumash Indians, California, based on collections by John P. Harrington. Economic Botany 44(2):236-253.