History:

to ~150M BC

Paleo-Ecology

The very first grasses have been documented to occur 83 to 55 million years before present (MYBP). These dates have been derived using molecular dating techniques, macrofossil evidence and/or fossilized pollen.

Development of the Grassland Biome

For many years, researchers thought that grassland biomes evolved ~ 30 MYBP in response to mammalian grazing (Wigand 2007). Evidence for this scenario was that grasses first began to diversify during this period: the fossil record showed rare fossils and pollen ~35 MYBP and molecular dating suggested an earlier diversification around 55 MYBP. Both of these estimates put development of the grassland biome well after dinosaurs had gone extinct (65 million years ago (Kellog 2001).

Special silicaceous structures in grass cells, called phytoliths, were hypothesized to be adaptations to avoid grazers.

Recently, however, analysis of fossilized dinosaur scat (called coprolites) tells a different story. Researchers looked for grass in 67-65 million year old coprolites. They not only found grass, but a diversity of grass types (Prasad, et al. 2005), indicating that grass diversification had occurred much earlier that previously believed.

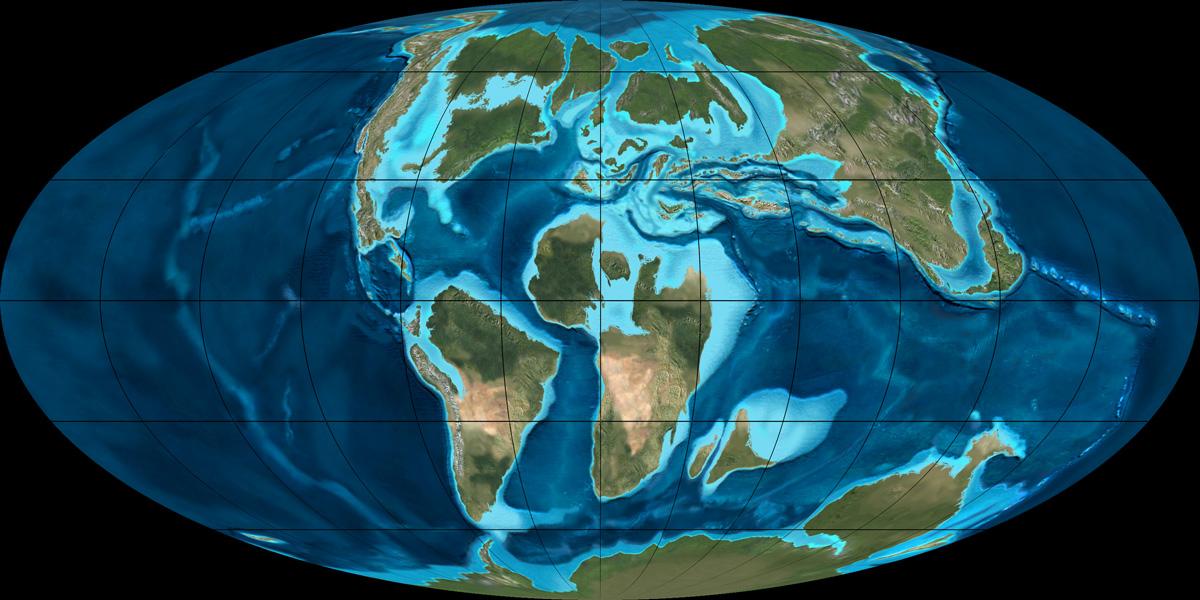

They proposed that grasses were diversifying as much as 80 MYBP, even before India had lost its connections with other southern continents. Most dinosaurs did not have dental features (such as grinding cheek teeth) to suggest they specialized on grasses – except for one group called sudamericid gondwanatherians that lived in South America, Madagascar, and India. This group had teeth suited for handling abrasive materials, such as grass.

While researchers previously believed that phytoliths—hard, microscopic structures found in some plant tissues—had evolved as a defense to mammalian grazing, some now believe they may have evolved in response to Cretaceous dinosaurs or insects (or have some other origin all together) (Prasad, et al. 2005).

Development of Grasslands and Coastal Prairies in California

Grasses first appeared in California during the Pliocene (5.3- 2.58 MYBP). The grasslands were generally mesic (moderately moist) and supported at least 19 species of plant-eating megafauna, as diverse as that of East Africa today (Wagner 1989). The broad plains of the wet California coast started to buckle and lift to form the coast range during the late Pliocene (1.6 to 5 MYBP).

The Pleistocene (2.58-0.012 MYBP) was a time of intense environmental change for California grasslands:

- The Mediterranean climate, with its hot dry summers, was established in California by the arrival of cold off-shore currents.

- Shifting of the North American and Pacific plates continued to uplift the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada.

- Pacific coast marine terraces are step-like landforms that are uplifted shore platforms that originally formed below sea level (Muhs, et al. 1992).

- Changing sea levels created the step-like coastal terraces, the foundation for coastal prairie communities, on California’s coast between 80,000 to possibly as much as 600,000 years old (0.08 to 0.6 MYBP) (California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz Chapter; Muhs, et al. 1992).

- The Pleistocene saw the full development of the megafaunal communities that began arriving during the Pliocene.

These dramatic changes created new regional, local and microclimate conditions. Many herbaceous (non-woody) annual and perennial plants in California evolved in the last 1 to 3 million years in response to these climatic and geological changes (Dallman 1998; Raven and Axelrod 1995; Solbrig, et al. 1977).

Coastal prairie plants evolved with the grazing, browsing, and trampling of large mammals (megafauna) during the Rancholabrean Period, from 300,000 to 11,000 years ago (Edwards 1992; Wagner 1989).

The Rancholabrean Age

The Rancholabrean Age is from 300,000 to 11,000 years ago and is named for the fossils found in the Rancho La Brea Tar Pits. It is one of nineteen time intervals in the “North American Mammal Ages” set by paleobiologists beginning 66.5 million years ago, and it ended with the demise of megafauna such as mammoths and bison. Some paleontologists place the beginning of the Rancholabrean at 150,000 years ago marked by the arrival of Bison in North American from Asia. Mammoths occupying the North Coast of California during the Pleistocene destroyed forests helping to convert them to grasslands; their wallowing behavior may have even created some of California’s vernal pools (Parkman 2006; Parkman c2011).

The dawning of the Holocene (12,000 YBP) brought yet another change: the arrival of humans and the end to an ecosystem dominated by grazing megafauna. The broad scale extinctions of these species have generally been attributed to hunting by humans, but the development of the Mediterranean climate may also have contributed to their demise (Edwards 2007).

Megafauna of Coastal Prairies and Grasslands (10,000 bp to 1.6 mybp)

“The diversity of carnivores and scavengers suggests, moreover, that the objects of their mutual alimentary interest—the megaherbivores—were not sparsely distributed in the landscape. They were abundant, and they were intensely active” (Edwards 1995).

It is hard to imagine the sheer number of plant-eating animals needed to support the carnivores that roamed California’s grasslands for prey. The size of the grazing/browsing populations must have had an immense impact on California grassland flora and ecosystem processes. By the late Pleistocene (10,000 BP to 1.6 MYBP), California grasslands supported one of the greatest wildlife assemblages on the Earth. The diversity and abundance of pre-historic grazers, browsers, predators and scavengers may be one of the greatest in the world exceeding that of East Africa (Edwards 2007).

The following list is a sampling of the grazers, browsers, carnivores and scavengers of Pleistocene grasslands (Edwards 1992; Edwards 2007; Parkman 2006; Wagner 1989). Many have been documented in Sonoma and Marin Counties (UCMP 2006). Species that are still extant are marked with an asterisk.

Grazers and Browsers

Note: Underlined Species are still extant today

- Elk (Cervus elaphus): mixed grazer-browsers eating about 50% grasses; the other 50% is mostly forbs.

- Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus): browsers.

- Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana): browsers.

- Two zebras (Dolichohippus sp., Pliohippus sp.)

- Giant horse (Equus pacificus)

- Western horse (Equus occidentalis)

- Three-toed horse (Neohipparion gidleyi)

- Large-headed llama (Hemiauchenia macrocephala)

- Brachyodont deer (Odocoileus brachyodontus)

- Pacific pronghorn (Antilocapra pacifica): a browser (Richards and McCrossin 1991).

- Dwarf antelope or four-horned pronghorn (Capromeryx minor; synonym: Breameryx): extinct browser less than 2 feet high in height with two-tined horns giving them a four-horned appearance.

- Shrub ox (Euceratherium collinum): browser-grazers about the size of a cow.

- Woodland musk ox (Symbos)

- Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi): stood over 12 feet tall and weighed over 10,000 pounds. Unlike modern Indian and African elephants, the Columbian mammoth ate primarily grasses (Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 2002).

- American mastodon (Mammut americanum): telated to but half the size of mammoths, mastodons were browsers eating primarily young twigs, leaves and shoots.

- Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani): a 3,500 pound grass grazer and browser(Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 2002).

- The Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis): the smallest of the ground sloths—about the size of a cow—was probably a browser, feeding on leaves, shrubs, and tree branches (Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 2002).

- Jefferson’s ground sloth (Magalonyx jeffersoni): a browser the size of an ox (Edwards 2007).

- Ancient or Ice Age bison (Bison antiquus): predominantly grazers with some browsing (Edwards 2007). A skull from Bison antiquus found in Sonoma County is at the University of California Museum of Paleontology. Ancient bison were migratory animals like their descendants, the modern bison. Migratory patterns were discovered by paleontologist analyzing the baby and permanent teeth determined the ages of the young bison remains found at the La Brea Tarpits; all fit into specific age groups fitting an annual pattern of migration that the animals were only there during the spring.

- Long-horned or giant bison (Bison latifrons): the largest bison with horns up to 7.5 feet were browser-grazers that went extinct up to 12,000 years before Bison antiquus (Edwards 2007) .

- Large or western camel (Camelops hestermus): larger than the modern camel this mixed grazer-browser consumed about 50% grass .

- Tapir (Tapirus): browsers.

- Flat-headed peccary (Platygonus compressus): an opportunistic feeder that browsed and rooted for bulbs but also killed small animals and foraged on carrion.

Carnivores and Scavengers

- Grizzly bear (Ursus arctos): extinct in California.

- Black bear (Ursus americanus)

- Gray wolf (Canis lupus)

- Mountain lion (Puma concolor)

- Short-faced bear (Arctodus simus). An omnivore that also ate plants, much like modern bears (Figueirido, et al. 2009).

- Flat-headed peccary (Platygonus compressus): an opportunistic feeder that browsed on vegetation and rooted for bulbs but also killed small animals and foraged on carrion.

- Merriam’s terratorn (Terratornis merriami): this large condor, with wingspans that could reach 12.5 feet (3.8m), was probably a common sight in the San Francisco Bay Area’s coastal plain.

- Dire wolf (Canis dirus): probably hunted in packs like modern wolves.

- Scimitar cat (Homotherium serum): lion-sized cats with small sabers.

- American cheetah (Miracinonyx trumani)

- American lion (Panthera leo atrox): larger than African lions.

- Jaguar (Panthera onca): present in California to 1826.

- Sabrecat (Smilodon fatalis): similar in size to African lions.

Small Carnivores and Scavengers Present Since Rancholabrean Times

- Coyote (Canis latrans)

- Bobcat (Lynx rufus)