Prairie:

Invasive Species

Common Invasive Annual Grasses of Coastal Prairie

Wild Oat (Avena fatua)

Slender Wild Oat (Avena barbata)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Annual native to Eurasia and North Africa.

- Species Interactions:

- The success of Avena lies in its superior competitive ability:

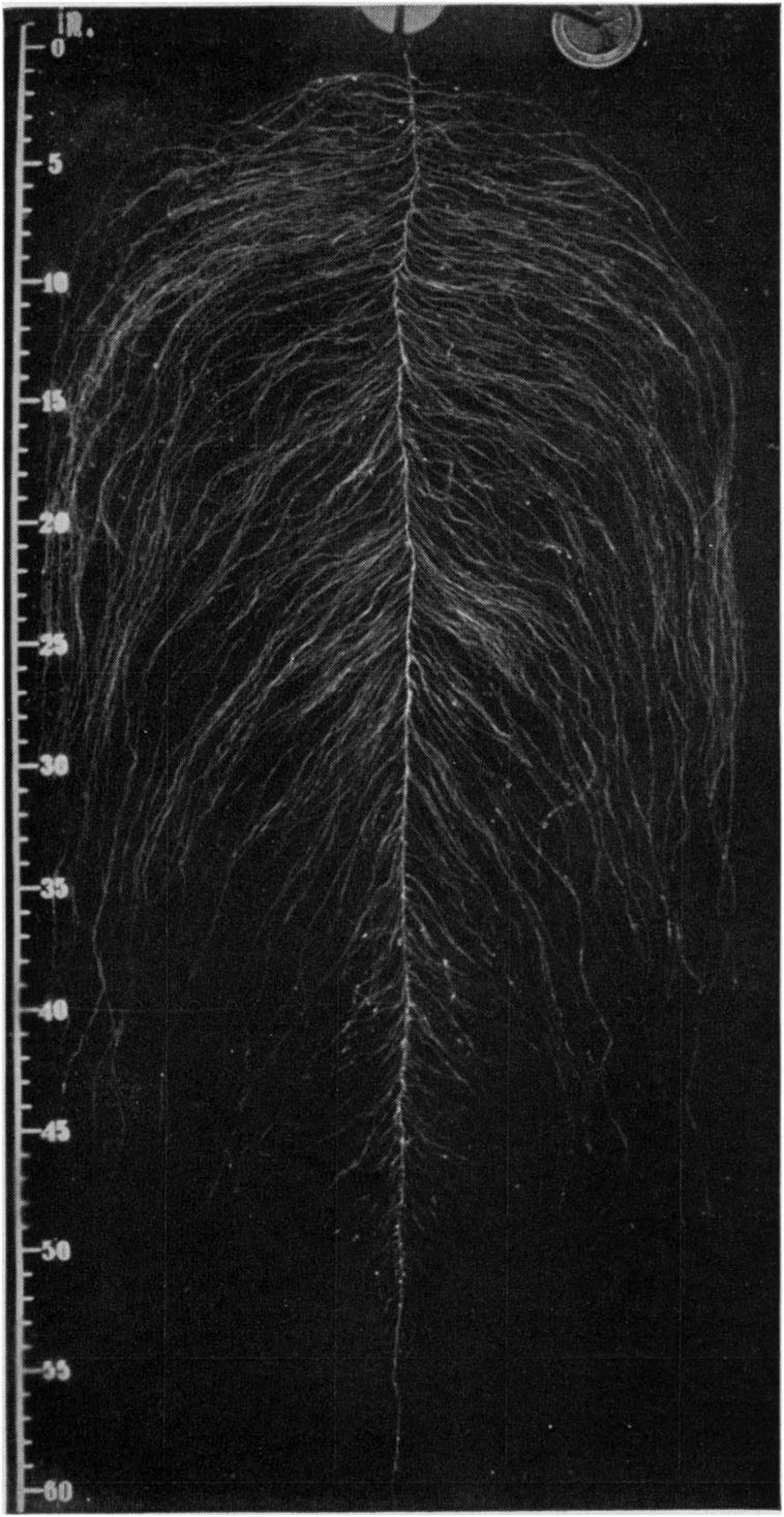

- It has a dense root system. The total root length of a single Avena plant can be from 54.3 miles long to, most likely, twice that long (Pavlychenko 1937; Dittmer 1937).

- It produces allelopathic compounds, chemicals that inhibit the growth of other adjacent plant species.

- It has long-lived seeds that can survive for as long as 10 years in the soil (Whitson 2002).

- Pavlychenko (1937) found that, although Avena is a superior competitor when established, it is relatively slow to develop seminal roots in the early growth stages (as compared to cultivated cereal crops wheat, rye and barley).

- The success of Avena lies in its superior competitive ability:

- Fun Facts:

- Avena is Latin for “oat.”

- The cultivated oat (Avena sativa, also naturalized in California) is thought to be derived from wild oats (Avena fatua) by early humans (Baum and Smith 2011).

- Wild oats were either introduced accidentally or as forage for cattle during the Mission Period (1769-1824) and have been widespread in California grasslands since that time (Hendry 1931).

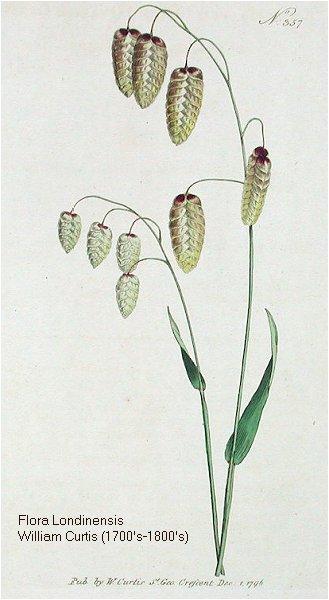

Rattlesnake Grass, Large Quaking Grass (Briza maxima)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Is a widespread annual.

- Can be dominant in grasslands in California and southern Oregon (California Invasive Plants Council).

- Is native to southern Europe.

- Fun Facts:

- Rattlesnake grass may be the earliest grass cultivated for ornamental rather than edible purposes (Snow, N. Utah State University c2001-2002).

- Rattlesnake grass escaped from gardens into the wild (Jepson c1902-1943).

- A lower stature, more delicate species, small quaking grass (Briza minor) is more widely distributed occurring in several states and in many habitats.

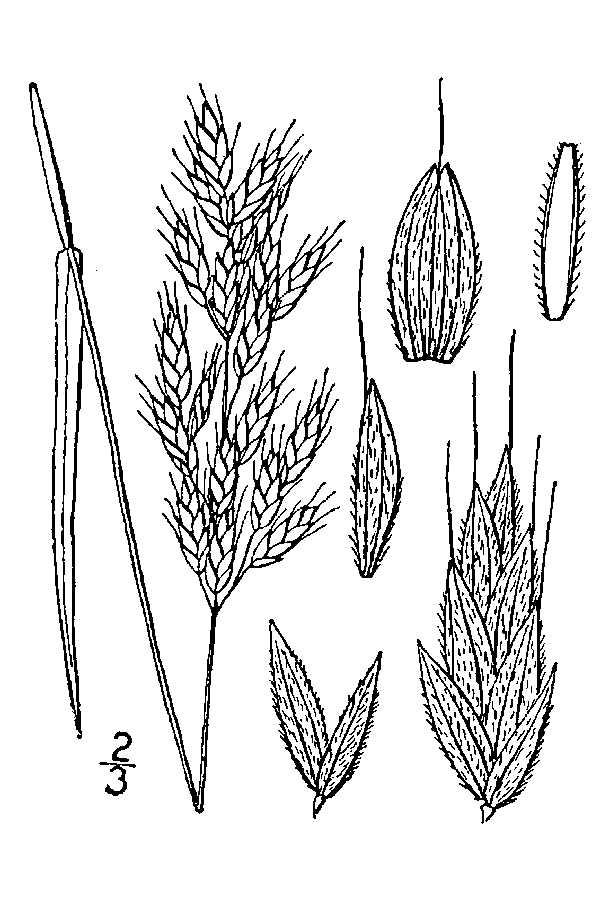

Ripgut Brome

(Bromus diandrus)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus) is a non-native annual.

- Is native in Southern and Western Europe.

- Along with red brome (Bromus madritensis), can be dominant in grasslands in California and other western States (California Invasive Plants Council 2011a; Minnich 2008).

- Life History:

- The long rough needle-like awns aid in dispersal.

- Seeds can be dispersed long distances by wind and water and by sticking to animals and people (California Invasive Plants Council 2011a).

- Fire:

- Ripgut brome has been implicated as one of many non-native grasses that have increased fire frequency in forests and shrublands, sometimes converting them to grasslands (Cal IPC).

- Fun Facts:

- Ripgut brome was introduced to California sometime around 1860.

- The needle-like awns can injure animals by penetrating their eyes, nose and mouth parts.

- Rip-gut brome sometimes looks a lot like the native purple needle grass. To tell the difference, hold a floret by the tips of the needle-like awns and run your finger along the awn toward the base of the floret. Purple needle grass is smooth while rip-gut brome has barbs that feel quite rough and catch on your fingertips.

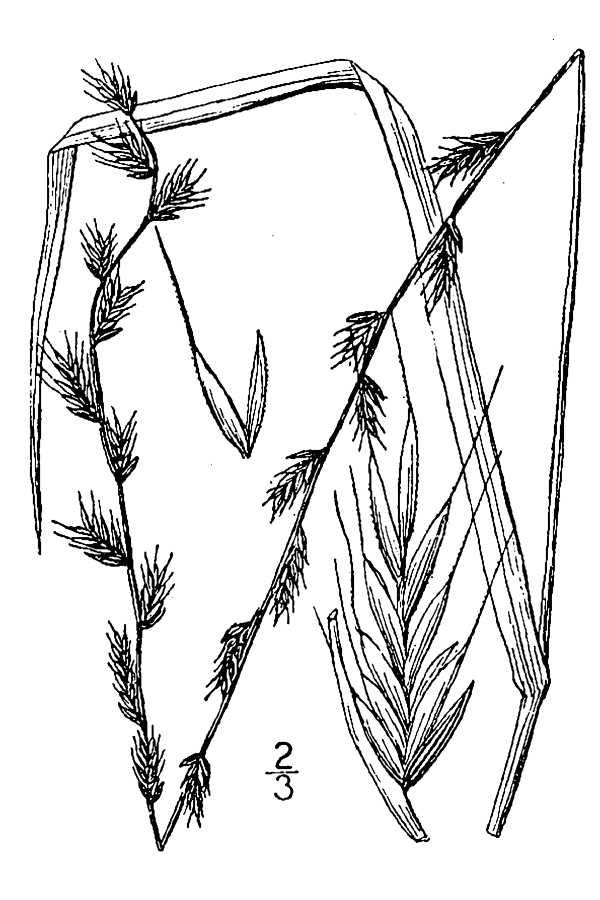

Soft Brome

(Bromus hordeaceus)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae)

- Is native to Eurasia.

- Has naturalized on all continents except Antarctica.

- Soft brome is abundant in coastal prairies (CPEFS 2010).

- Grazing: Soft brome was introduced as a forage species, although there are conflicting accounts of its nutritive value and palatability.

- Life History:

- The seeds are short-lived (Howard 1998).

- Bromus seeds readily germinate under mulch layers. Therefore the plant litter accumulation that occurs in the absence of fire and grazing tends to increase Bromus populations at the expense of native annuals and perennials whose germination is suppressed by litter (Heady 1988).

- Species Interactions:

- Soft brome threatens rare grassland species because it can outcompete them in the areas of infertile and serpentine soils that act as refuges for many rare plants (California Invasive Plants Council 2011b).

- Fun Facts:

- Soft Brome Is more abundant in the Mediterranean areas of California than in its native range in Mediterranean Europe (Howard 1998).

- Bromus hordeaceus was previously called Bromus mollis and is also known by the common name soft chess.

Mouse barley, foxtail barley, hare barley, farmers foxtail

(Hordeum murinum)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Is native to Eurasia

- Now occurs in every county in California (Calflora 2010).

- Life History:

- A common weed in disturbed sites in its native Eurasia, Mediterranean barley’s origins are thought to be around seasides, sandy riverbanks, and animal watering holes (Utah State University c2001-2002).

- Species Interactions:

- The Kashaya Pomo, Ohlone, and the Mendocino Indians made use of this introduced annual grass by harvesting and eating the seeds of Hordeum murinum (Bocek 1984; Chesnut 1902; Goodrich, et al. 1980).

- Fun Facts:

- More common than Mediterranean barley (H. marinum), this annual from Eurasia may have been brought by the Spanish settlers in California (California Invasive Plants Council).

A Couple More…

Mediterranean barley

(Hordeum marinum subsp. gussoneanum)

Non-Native

- Mediterranean barley (Hordeum marinum Huds. subsp. gussoneanum) is an introduced annual from Eurasia. Although similar to mouse barley (H. murinum), it is less abundant in coastal prairies and in California as a whole.

Purple false brome

(Brachypodium distachyon)

Non-Native

- Wiry culms, sparse foliage, and stiff-awned seed heads make purple false brome poor forage for livestock (Crampton 1974:77).

- This introduced annual grass is considered a model organism for research because of its small genome, short lifecycle & stature, is self-fertile and because it is closely related to the major grain crops (wheat, corn, etc.) (http://www.brachypodium.org/).

Common Invasive Perennial Grasses of Coastal Prairie

Italian ryegrass

(Festuca perennis, formerly Lolium perenne)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Italian ryegrass is a European annual or short-lived perennial tufted grass.

- Is found in wetlands, grasslands, and disturbed sites (Holloran, et al. 2004).

- Is now common in coastal prairies.

- Life History:

- Seeds germinate readily leaving few in the seed bank (Holloran, et al. 2004).

- Species Interactions:

- The plants leave a thick layer of dead leaf litter on the soil each season which can inhibit the germination of other species.

- Drought:

- Roots can extend 3 or more feet into the soil on dry sites (Holloran, et al. 2004).

- Fun Facts:

- Italian ryegrass was cultivated in Italy from at least the 13th and 14th centuries (Carey 1995).

- Italian ryegrass often escapes into grasslands from cultivation where it is grown as livestock forage and as a turf grass (California Invasive Plants Council).

- It was for many years the most commonly used species for erosion control in the coastal areas of California (Carey 1995).

- Increased soil fertility from nitrogen deposition in auto exhaust has been linked to the increase of Italian ryegrass in serpentine grasslands—grasslands with harsh, nutrient poor soils that often are refuges for native plants—in the San Francisco Bay area (Harrison and Viers 2007:154).

- Taxonomic Note:

- Perennial ryegrass (formerly Lolium perenne) and annual ryegrass (formerly Lolium multiflorum) were considered as separate species in the First Edition of the Jepson Manual (Hickman 1993). Some authors considered them both as subspecies of Lolium perenne (L. perenne ssp. multiflorum and L. perenne ssp. perenne). The Second Edition of the Jepson Manual (2012), moves them from the genus Lolium to the genus Festuca and combines them into a single species: Festuca perennis.The authors note that what was once thought to be the differentiating feature—awned or awnless florets—can often be found on the same plant. Annual ryegrass is described as having bristle-like awns on lemma tip (a lemma is the lower of two bracts that subtend the floret) while perennial ryegrass is awnless. It may be that the perennial or annual habit relates to the availability of summer water, with the plant acting as a perennial when water is available. Regardless, the plants are found in coastal prairie habitats.

Sweet vernal grass

(Anthoxanthum odoratum)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass family (Poaceae).

- Sweet vernal grass is a tufted perennial grass.

- Is native to Europe.

- Is widespread in the United States and other temperate climates (University of California 2009).

- Is distributed from Santa Barbara through Del Norte Counties and common in coastal grasslands in northern California.

- Fun Facts:

- This species escaped from cultivation as a meadow grass.

- It is named for its sweet vanilla-like odor from a chemical compound called coumarin, that has a bitter taste and, in large quantities, can cause hemorrhaging in cattle (University of California 2009).

Common velvet grass

(Holcus lanatus)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass family (Poaceae).

- Is dominant in many of California’s coastal prairies (Sawyer, et al. 2009).

- Drought:

- Holcus lanatus and other non-native perennials have the ability to use summer fog to extend its growing season much like California’s native perennials (Corbin, et al. 2005).

- Grazing:

- Holcus lanatus is cultivated for forage and hay (Jepson Manual 2012).

- Livestock do not prefer the soft velvety foliage but will graze it before the seed stalks appear” (Sampson et al. 1951)

- Tule elk at Point Reyes National Park graze on Holcus lanatus from August to December, during which time it comprises from 15 to 41 % of their diet (Grogan & Barrett, 1995).

- Holcus has more protein than perennial ryegrass, a common forage species often planted by ranchers. Harrington and others (2006) found that Holcus had 295g per kg of dry matter of crude protein compared to 232g/kg for ryegrass.

- Life History:

- Viable seeds can persist in the seed bank 5 to not more than 20 years (Bond et al. 2007).

- Species Interactions:

- Holcus lanatus impalatability to sow bugs, also introduced, leads to increased litter accumulation in grasslands (Bastow, et al. 2008).

- Sampson and others (1951) suggest that Holcus lanatus is an early successional plant that is “often replaced by more desirable forage species when ranges are grazed conservatively.”

- Velvet grass seed is abundant and has become a "key" food for California quail (Callipepla californica) (Gucker 2008).

- Holcus lanatus is not resistant to trampling and populations can be decreased by heavy, sustained trampling (Bond et al. 2007).

- Fun Facts:

- Holcus lanatus probably originated on the Iberian Peninsula in Europe (Jacques, 1974).

- Holcus lanatus was introduced from Europe and already widespread in North America by 1800 (Utah State University c2001-2002).

- Holcus lanatus is cultivated for forage and hay (Jepson Manual 2012).

- With the arrival of invasive perennial grasses, such as common velvet grass, coastal prairies may be undergoing the most significant change in species composition since the arrival of Europeans (Corbin, et al. 2005).

- The Coastal Prairie Enhancement Feasibility Study and others are working to find ways to control Holcus lanatus. Seedlings can be pulled easily, but mature plants develop dense fibrous roots that bind the soil and make removal difficult. The easiest time to pull adults is in late summer when the plants go dormant (Kathleen Kraft, personal communication). Mowing treatments are effective in controlling seed production but can stimulate spread through tillers.

- For information on controlling Holcus lanatus see the Cal-IPC (California Invasive Plants Council) website and the Weed Workers Handbook (Holloran, et al. 2004).

- Holcus mollis (creeping velvet grass) is a rhizomatous grass that is also introduced from Europe, sometimes sold as an ornamental, and is a problem weed in prairie remnants and oak savannahs in the Pacific Northwest (Utah State University c2001-2002). There is one specimen on file for Sonoma County (collected on Bayflat Road, Bodega Bay in 1990) and three for Marin County (1969, above Tomales Bay; 1974,near Marshall on Hwy 1; 1977, Point Reyes south of Inverness)according to the Consortium of California Herbaria. However, the species is not listed in the Marin Flora (Howell et al. 1997).

Hairy oat grass, poverty Grass, hairy wallaby grass

(Rytidosperma penicillatum, formerly Danthonia pilosa)

Non-Native

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Hairy oat grass is an introduced perennial bunchgrass.

- Is native to Australia.

- Grazing:

- This perennial bunch grass is considered of economic importance as animal forage in Australia and in New Zealand (USDA GRIN (Germplasm Resources Information Network, cited 15 Oct 2010).

- Fun Facts:

- Introduced and grown experimentally in California and in several other states, hairy oa tgrass is now considered a troublesome pest in coastal areas of California and southwestern Oregon (Jepson Interchange. Cited 15 Oct 2010 ).

Andean tussock grass

(Stipa manicata, formerly Nassella manicata)

Non-Native, Recent Invader

- Member of the Grass Family (Poaceae).

- Is native to Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay.

- Is established in Sonoma, Monterey and Calaveras counties in California (USDA NRCS 2010; Utah State University c2001-2002).

- Fun Facts:

- It was introduced and established in California in areas associated with sheep grazing. It was misidentified as N. formicarum in the Jepson Manual (1993).

- Andean tussock grass resembles the California native purple needlegrass (Stipa pulchra, formerly Nassella pulchra), but has shorter florets and more developed crowns (Utah State University c2001-2002).

- Other scientific names previously used for this species include: Stipa manicata, Nasella formicarum.

Common Invasive Forbs of Coastal Prairie

Italian thistle

(Carduus pycnocephalus)

Non-Native

- Member of the Sunflower family (Asteraceae).

- Is an annual native to the Mediterranean regions of Eurasia and northern Africa (Bossard, et al. 2000).

- Drought:

- A single plant can produce 20,000 seeds (Bossard, et al. 2000).

- Seeds germinate readily with fall rains and are quick to colonize areas where vegetation has been removed, such as after fire or in pastures that have been overgrazed and excessively trampled (California Department of Food and Agriculture. Accessed 2010 Oct 24).

- Italian thistle is a poor competitor with established perennial plants (California Department of Food and Agriculture. Accessed 2010 Oct 24).

- The plants grow from basal rosettes of leaves that cover the ground blocking the growth of other species (Bossard, et al. 2000).

- This species was accidentally introduced into California between 1912 to 1930 (Bossard, et al. 2000).

Burclover

(Medicago polymorpha)

Non-Native

- Member of the Pea Family (Fabaceae).

- Burclover has a clover-like leaf with three leaflets and yellow pea-like flowers, but it is not a true clover (Trifolium).

- Is an annual native to the Mediterranean region.

- Life History:

- The spirally coiled bur-like fruits stick to animal fur and to the socks and shoes of humans who help to spread the seeds.

- Drought:

- Jepson (1922, as Medicago hispida) says of burclover, “By cattlemen the plant is prized as a dry season stock feed, since the burs are produced in great quantity and are highly nutritious; it also furnishes a green pasturage in the rainy season. This is a rare instance of an aggressive immigrant herb having a high economic value.”

- Fun Facts:

- Medicago polymorpha is so widespread in California that its common name in the Jepson Manual is California Burclover (Isley 1993).

- Burclover was most likely brought into California in the wool of sheep accompanying the Spanish Missionaries (Hendry 1931; Jepson c1902-1943).

Common, rough or hairy cat’s ear, false dandelion

(Hypochaeris radicata)

- Member of the Sunflower Family (Asteraceae).

- Cat's Ear is a perennial dandelion-like forb.

- Is widespread in coastal terrace prairie.

- Can be one of the more dominant species in coastal terrace prairie (Warner, P. 2003).

- Grazing and Fire:

- perennial that produces many seeds annually.

- It has a thick fleshy tap root in which it stores energy to resprout.

- The plants basal leaves, arranged in a rosette, spread over the soil obstructing other plants from growing around it.

- Maria Copa: leaves eaten with salt (57).

Hairy hawkbit

(Leontodon saxatilis, formerly Leontodon taraxacoides)

Non-Native

- Member of the Sunflower Family (Asteraceae).

- This dandelion-like plant (Leontodon means “lion’s tooth”) looks and behaves very much like hairy cat’s ear (Hypochaeris radicata). It is prevalent in the coastal prairies that are nearest to the ocean.

- Introduced from Europe, there are two subspecies in California: L. saxatilis subsp. longirostris and L. saxatilis subsp. saxatilis. Both occur in disturbed areas.

English plantain

(Plantago lanceolata)

Non-Native

- Member of the Plantain family (Plantaginaceae).

- Is native to Europe.

- Is wildly successful in cismontane California.

- Species Interaction:

- Tom Smith, Bodega Miwok, told Elizabeth Kelly that Plantago lanceolata, called súgui-kole, or just kole, was used for house thatching by placing the root end up (Kelly 1996).

- Tom Smith added that after the Spanish came, the women saved and planted the seeds by scattering them on the ground.

- Plantain (P. major, also native to Europe ) was used medicinally by several groups in Mexico, Baja, and New Mexico (Timbrook 2007), but Tom Smith does not mention any medicinal use by the Bodega Miwok.

- Chesnut writes that the Mendocino Indians did not use the plant although it covered the valley and that it was grazed only sparingly by cattle.

Red-stem filaree, red-stem stork’s bill

(Erodium cicutarium)

Non-Native

- Member of the Geranium family (Geranaceae).

- Is native to Mediterranean region (Mensing and Byrne 1999).

- Life History:

- The barbed corkscrew-like awns on the fruits can launch seeds up to a half meter from the plant.

- The awns bury the seeds by drilling into the ground as they wind and unwind with changes in humidity (Evangelista et al 2011).

- Fun Facts:

- Red-stem filaree may have been one of the earliest weeds introduced into California. Native to the Mediterranean region, it was probably first brought to Baja California in the 1750s and moved north with the pre-Mission Spanish explorers, its barbed corkscrew-like seeds stow-a-ways in the fur of livestock and as a contaminant in feed (Mensing and Byrne 1999).

- There are only two native Erodium species in California in the Jepson Manual (Hickman 1993). Erodium macrophylla, the only native Erodium that occurs in coastal prairies was recently reassigned to a new genus as California macrophylla being segregated from Erodium on morphological, molecular data. The genus is named for the California Floristic Province (Jepson Interchange for California Floristics. Accessed 14 Nov 2012).

Animal Invaders of Coastal Prairie

The most visible animal invaders in coastal prairies are feral pigs (see below). However, exotic animals of all sizes have found a home in coastal prairie. Even the smallest of introduced species can have big effects on community structure and composition.

Feral Pigs and Wild Boars

(Sus scrofa)

"Pigs' effects may typify the complicated events to be expected when an ecosystem's regime of disturbance is significantly altered."

Right: Male pig at a farm in England. 27 August 2008. Amanda Slater. Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gloucester_Old_Spot_Boar,_England.jpg

- Member of the Pig Family (Suidae).

- The Wild Boar/Feral Pig crosses of California have the typical large heads, and tusks (males) of their wild ancestors, but show a range of patterns in black, brown and white more typical of domestic pigs.

- Is native to northern and central Europe, the Mediterranean region and Asia south to Indonesia.

- Were established in California in the 1800s around coastal Spanish settlements and expanded over the last century by hunting introductions of wild boar, domestic pig releases, and natural dispersal (Sweitzer and Van Vuren 2009).

- Occupy a wide range of habitats, including grasslands; their range is largely coincident with oak woodlands in California due to their dependence on acorns and cover (Sweitzer and Van Vuren 2009, Massei and Gunov 2004).

- Soil Disturbance:

- Rooting, which occurs at an average depth of 5-15 cm, can cause 80-95% reduction in herbaceous cover, cause the severe reductions or local extinction in some plants and animals, and reduce the density of seedlings by 1.5 to 6 times (Massei and Gunov 2004).

- In areas of high pig density, rooting can occur at least once per year on 74 to 80% of the soil surface and cause increased erosion on steep slopes, and nutrient leachng (Ca, P, Zn, Cu, and Mg) (Singer 1982). Although in a 4-year pig exclosure study in California grassland, Cushman et al. (2004) found no evidence that pig disturbances affected nitrogen mineralization rates or soil moisture availability.

- Areas that have been rooted by Wild Boar show greater rates of organic matter decomposition, and can create more vigorous growth in plants that survive (Massei and Gunov 2004).

- Wild Boars may serve as a dispersal agent for some plants. Seeds can pass through their digestive tract unharmed, and they have been shown to disperse seeds of invasive plants (Massei and Gunov 2004).

- Species Interactions:

- Pig rooting may enhance colonization by non-native grasses and forbs. Based on the results of 4-year pig exclosure study in California grassland, Cushman et al. (2004) hypothesized that clearing by pigs provided greater opportunities for colonization and reduced intensity of competition for non-native plants.

- Pig rooting may also prevent the colonization of grasslands by shrubs and trees: pig rooting significantly decreases colonization by oak seedlings in the understory of oak woodlands (Sweizer and Van Vuren 2009).

- Plants comprise 80% to 90% of the diet of wild boar. Pigs spend most of their time rooting for tubers, roots, bulbs and often eat fruit, fungi, and acorns (Massei and Genov 2004). Their rooting can cause 80-95% reduction in herbaceous cover and declines in preferred species (Massei and Gunov 2004).

- Animals are found in 97% of pig stomachs sampled and comprise 2-11% of the diet volume. Invertebrates, such as insect larvae, earthworms, and snails are regularly consumed. Seven years after removal of feral pigs, the total density of microarthropods in a forest nearly doubled and biomass increased by 2.5 times. Impacts to small vertebrates consumed, such as carcasses, small rodents, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, have also been found for ground-nesting birds, surface-tunnelling rodents, and small insectivores (Massei and Gunov 2004).

- Where large carnivores are present, wild boar invariably appear in their diet and sometimes are one of the most important prey. Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) recolonized the California Channel Islands with availability of pigs as prey and subsequently started to prey heavily on the native island fox (Urocyon littoralis), causing drastic declines.

- Fun Facts:

- Between the 1960s and mid 1990s, Wild Boar populations expanded from about 10 coastal counties to over 50 coastal counties in California. As of 1996, 25% of the total land area of California was occupied by Wild Boars and they were most abundant in the central and north-coast regions (Waithman et al. 1999).

- Wild boars have the highest reproductive rates among ungulates and, in areas with abundant food supply, are capable of 150% annual increases in population size (Massie and Genov 2004).

- The extent of rooting and the density of Wild Boar populations are directly correlated (Massei and Genov 2004).

Sow bugs

(Porcellio scaber)

Non-Native

- Sowbugs are crustaceans (order Isopoda) that consume plant debris.

- Are native to western Europe.

- Species Interaction:

- Sow bugs are an important detritivore in coastal grasslands (Bastow, et al. 2008).

- The impalatability of Holcus lanatus to sow bugs leads to increased litter accumulation in coastal prairies (Bastow, et al. 2008).

- Fun Facts:

- Sowbugs have been present in California for over a century (Bastow, et al. 2008).

- It is not known if there were native terrestrial isopods in California prior to European contact.

Slugs and Snails

- Introduced slugs and snails are major pests in California croplands. Slugs and snails eat seeds, leaves, and other plant parts and can consume and kill seedlings. Researchers are just beginning to discover that slugs and snails can have large effects on wildland plant communities (Maze 2009; Strauss, et al. 2009). California has a rich variety of native slugs and snails.

Note: The scientific names for the plant species are taken from the Jepson Manual of Vascular Plants of California, Second Edition (Baldwin et al. 2012).