Management:

Restoration

How to Manage and Restore Coastal Prairie: Thoughts from the Field

Grasslands are Dependent on Disturbance

Grasslands are disturbance-dependent ecosystems: their maintenance depends on fire, grazing, or other disturbance. The regular wildfires and abundant wild grazers that once shaped and sustained grasslands are now a thing of the past. Today, land managers must make decisions and implement actions in order to maintain grasslands as healthy, functioning ecosystems.

California’s remaining coastal prairie grasslands that are not yet threatened by urban and agricultural development face the threats of being enveloped by woody plants and/or overrun by weeds. Neither of these outcomes is desirable. The loss of grasslands to encroaching shrubs and trees, even if they are native woody plants, reduces habitat for grassland dependent plant and animal species and reduces the extent and quality of pasture for domestic grazers. The replacement of native grassland plants by exotic weeds can degraded animal habitat, decrease forage quality by an increase in the amount unpalatable plants, and result in an overall decline in biological diversity.

The focus of this section is to demystify the process of management and restoration. We know that if left alone, grasslands will disappear. But what kinds of disturbance? How often? How much?

Unfortunately there are as many answers to these questions as there are grasslands existing in micro-habitats. While we can't provide a comprehensive complete answer to these questions, we can provide a framework for getting you started in enhancing coastal prairie on your land.

Myths About Management

First, let’s dispel a few myths. It’s best to get these out of the way, since you can really lose a lot of time mucking around thinking that perhaps you just didn’t search hard enough to find answers to these management Will o’ the Wisps.

Myth: If we restore historic disturbance regimes, we will restore coastal prairie.For many years, land managers sought to determine what the historic disturbance regimes used to be and to reapply them (e.g., we just have burn at the frequency that Native Americans burned or re-introduce elk and we will get beautiful coastal prairies). Unfortunately, although this may have worked 300 years ago, it will no longer work today. The species (new invaders), climate, and the amount and distribution of available habitat have changed significantly. Burning grasslands today, if done at the same frequency, timing and intensity could keep out shrubs and trees, but could also enhance the growth of non-native species relative to native species. Instead, grazing, burning, and other disturbances need to be viewed as tools to achieve specific goals.

Myth: What works on my neighbor’s land will work on my land. While this always a good place to start, remember that no one out there has a situation just like yours. Even different sites on your own land will respond differently to the same treatment. Variation in aspect, slope, soil, and species occurrences all have significant effects on the outcome.

Myth: Researchers have figured all this stuff out. Many newcomers to the field start out thinking that researchers have already figured out how to maintain or restore native species. But, while there is some great information available and some good success stories, far less is known than you might think. Instead, it is more useful to imaging yourself as entering a new community of explorers who are trying to understand the vagaries of management. Here are some great resources that will help you start down that path:

- California Grasslands:Ecology and Management – Mark Stromberg et al. 2007. University of California Press.

- Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge and the Management of California’s Natural Resources – Kat Anderson. 2005. University of California Press.

- Grazing Handbook: A Guide for Resource Managers in Coastal California - Lisa Bush. Sotoyome Resource Conservation District

Myth: What works this year, will work next year. Weather happens. Each year, we experience differences in the timing and abundance of rainfall and temperature. Some years will be a good year for species A and bad year for species B, and in other years it may be vice versa. This variability means that managers need to embrace and, need we say it, even enjoy the challenge of year to year variability. Each year brings unexpected results, and if you take the time, it can serve as a window for understanding the workings of nature.

Myth: Fire is fire and grazing is grazing. “Burning” or “grazing” are practically misnomers when it comes to describing management and restoration techniques. It is not so much that you burned or grazed, but rather when you did it, how intensive it was, whether it was spotty or uniform, and, in the case of grazing, which species did the eating (e.g., elk, cattle, goats, sheep, deer, etc.). All of these factors can influence how your grassland responds to treatments.

Myth: I’m on my own. You are not the only one trying to figure out an approach to enhancing coastal prairie habitat on your land. There are many folks out there that you can work with, take classes from, or even get together with to trade strategies. We recommend you contact your local Resource Conservation District and become a member of organizations who regularly have classes and workshops. Not only are you not on your own, but once you take the first step in managing your lands, you essentially become an expert on your lands, trading ideas and strategies about what works and what doesn’t work.

Species-Specific Approach for Enhancing Natives

Coastal prairie is composed of individual species of grasses, forbs, insects, etc. Each of these species responds is a slightly different way to the world around it. It is these differences that form the basis for setting management and restoration goals.

A species-based management approach is a great way to quickly introduce the basic concepts that all managers need to develop a management plan. We provide it here, not as an encyclopedic resource for coastal prairie management and restoration, but as a tool for you to develop a management approach that works on your lands. This approach is not novel, but it is interesting that some managers today still apply management prescriptions without fully considering which species are present in their grasslands.

We hope these pages will provide you with the tools (and creativity!) to devise and revise approaches to coastal prairie restoration and management. As this cherished resource is disappearing, each of needs the tools to undertake our own efforts, whether that is the postage stamp of our own backyard or a 10,000-acre ranch or reserve.

1. State Your Goal

Be clear about what you would like to accomplish in your grasslands. Landowners and managers may have a variety of goals they would like to achieve. This can lead to some confusion unless you are clear on what you want. Examples of goals include:

- Create high-value forage for domestic livestock

- Create habitat for wildlife

- Create open space

- Maintain firebreak around your home

- Create a visually appealing prairie with high diversity of grasses and forbs

2. Identify the Grasses and Grassland Forbs on your land

One of the best places to start identifying species is the grasses themselves. The complexity of this task will vary depending on the condition of your grassland. If your grasslands are relatively intact (e.g., have never been plowed), one or two native grasses will likely be dominant. At sites that are more degraded, the field may have 15-20 species non-natives grasses. That is not such a handful to learn.

Grasses are easiest to identify when they are flowering. In California, the month of May is one of the best times to be out learning about grasses. If keying out plants doesn’t appeal to you, don’t worry as most grasses can be identified without rigorous keying and study. Many people know the species on their property by general appearance alone. If you would like to do this as well, here are a few pointers:

Grasses have flowers and other parts. Begin by learning some of the names of the flower parts. Find yourself a diagram (there are many in books and on the web) and see if you can identify how these parts are different in each species. There are also classes you can take at your local California Native Plant Society or with the California Native Grassland Association.

Even if you don’t know the names of the species on your property, you can still figure out what you have by collecting as many different kinds as you can see. Once you start looking, it is pretty easy to see what is the same and what is different.

Tape leaves and flowers to cardstock using clear packing tape. If you think a species may be unusual or rare, you can take a picture instead.

You will need to know the names of your species(scientific names are best because they are standardized) so that you can find out information about them. To identify your species, there are a variety of online sources:

- University of California Integrated Pest Management Program has excellent website with terminology and the identification of grasses.

- CalPhotos is a collection of over 320,000 photos of plants, animals, fossils, people, and landscapes from around the world.

- Sonoma Land Trust's Sonoma County Coastal Prairie Flora: Estero Americano Preserve Herbarium Book is a great resource for species in Sonoma and Marin County.

- California Native Plant Society has created a series of 4 laminated placemats with native and non-native grasses. These are a great place to start for beginners, since it presents drawings of the most common species all in one place.

- Ask a friend. Attend a grassland identification workshop. The California Native Grassland Association (CNGA) regularly offers workshops on grassland identification.

Find out which species are native and which are non-native. This information is available on a variety of on-line resources and in books. If your land has been tilled in the past, it is highly probably that most of your species are non-native or weedy natives.

3. Choose the Worst and the Best Species

It’s time to figure out which species are causing the problems and which ones are desirable. Determine which species:

- are the worst invaders. Do you have any species on your property which are forming monocultures, crowding out any native species? If so, these are the ones that are the most problematic. Examples include velvet grass (Holcus lanatus), tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), medusa head (Taeniatherum caput-medusae), ripgut brome (Bromus diandrus).

- used to be native dominants of coastal prairie in your area. The high diversity of coastal prairies is provided by forbs, but native grasses usually dominate (i.e., have the greatest surface coverage). Coastal prairies are often dominated by only 1-3 native grasses. These once-dominant species can still persist in patches or as subdominants. Trying to reinvigorate native grasses to form a dominant canopy while flowering is great place to start.

In some cases, you may have only weedy fields with no native grasses or forbs on your property. This may indicate that your property has been plowed or tilled in the past. Almost all of our native grassland plants have a very poor ability to recolonize areas when non- native species are present. Areas that once were tilled show this long-term legacy. If this is the case on the land you would like to restore, you will need to find an area nearby that is similar to your property and that may provide clues regarding which species once thrived in your area.

4. Get to Know Your Target Species

You will need to find out key aspects of the biology of your invaders and your native species. Your challenge is to devise a strategy that will hinder reproduction and survival of the invaders relative to the desirable natives. Often these treatments are a bit like chemotherapy: we’re looking for something that may hurt all the plants, but will hurt the invaders more than it hurts the natives.

There is no single source of information for all species, and you may have to search for the information on the web, in the library, and perhaps even in the scientific literature. A couple of our favorites for detailed information about grassland species are:

Not every species will be in these databases, but many are. These wonderful databases provide a wealth of information about each species and often the key pieces of information you need (below) can be easily extracted. And always remember, if you can’t find it in a book, you go outside and make your own observations.

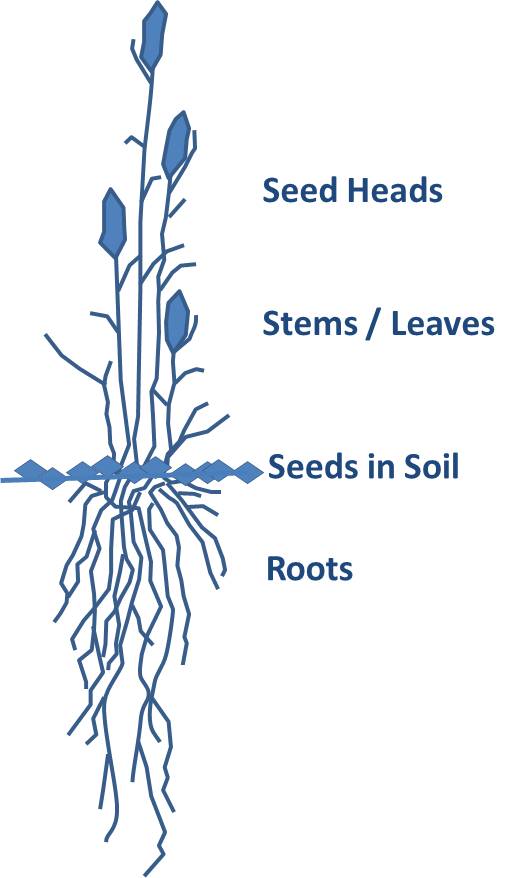

There are five basic types of information you need to know about each species to begin the process of devising a management or restoration plan: longevity, seed heads, seeds in soil, vegetative growth, and roots.

Longevity

Annuals or perennials?. Annuals are completely reliant on the seed bank (seeds in the soil) for persistence. Each year, they germinate from seed, grow quickly to adulthood, produced seeds and die. Perennials can live from a few years to centuries.

In case you are wondering how to tell them apart, perennial grasses look very similar to annuals during the first year of life. But you can pick them out as soon as they are two years old – they are the plants with the green leaves growing out of the dead leaves.

There are a number of traits that are related with the two strategies that are regularly used by managers to enhance coastal prairie:

- Annuals: tend to grow quickly, bloom early, have shallower roots

- Perennials: tend to grow slowly, bloom late, have deep roots

Seed Heads

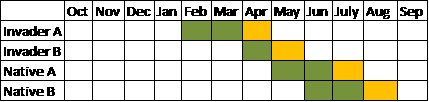

Reduce seed production of invasive target species without reducing seed production of native target species. Knowing when the seeds of your invaders and native target species mature can help you develop a plan. If there is a difference in the timing of seed maturation, you have a chance to differentially reduce seed production in these two species.

Example: You can search the literature to find out when each species flowers and sets seed. Many natives bloom and set seed later than non-natives, so this can be useful information. Remember though that each year is different, so you’ll want to keep track of which species on your land is setting seed and when. Remember too that the same species growing on a hot south-facing hillside can set seed much earlier than the same species growing near a riparian zone or on the north-facing slope.

The management tactics for the situation above would be to remove all of the seed heads in your grassland (grazing, fire, mowing, hand pulling) in late April, just before the invaders have set seed, and just before the natives begin to flower. Basically, your hope here is that the late season perennial natives will be able to recover from your treatment and set more seed that the early season annual invaders.

In the example above, you would need to remove the flowers of Invader A by the end of March before seed set. Since Invader B might still be growing more flowers in April, you might consider a second flower removal effort at the end of April. Hopefully both Native and A and B will be able to continue growing in June and achieve seed set in July and August.

Of course reality is rarely so clear, but the basic idea is that you are looking for the “sweet spot” in the timing of flower removal, where you will decrease invader seed relative to native seed production. A couple things to note:

Most plants can continue to grow new seed heads after the initial seed heads are removed. For this reason, it is best to plan to remove seed heads as late as possible in the year. If the weather is dry enough, the plants do not have the moisture needed to re-grow many seed heads after grazing, mowing or fire has ceased.

When stems and seed heads regrow, they often grow more laterally. If you decide to do a follow up treatment to remove the regrown seed heads, you may want to make sure that your second treatment (whether the same or different) will work with low-growing and spreading growth (e.g., mowing may not work effectively, but intensive grazing might be able to).

Seeds in Soil

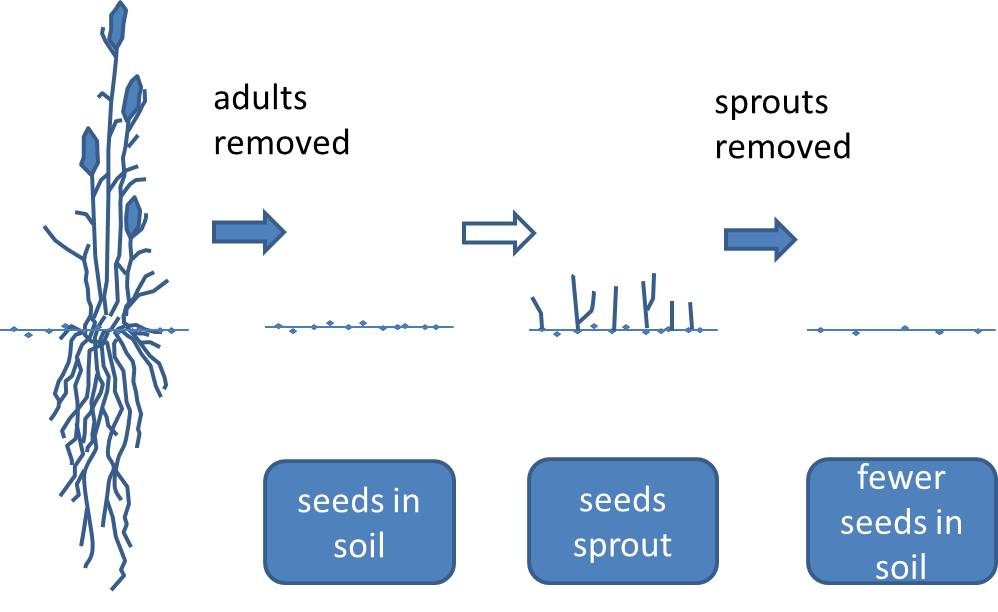

Plan for the germination of seeds in the soil. Often someone who has applied a single treatment to remove adult weedy invaders is unpleasantly surprised to find the densest patch they have ever seen of that same invasive plant growing in the same place the following year. It is not that their initial treatment did not work, but rather that they did not follow up with a treatment that targeted the seed bank or seedlings. Managers have tried a number of approaches working with seedbanks.

Removing seeds you don't want

- Wait for them to die – This is one of the only ways we know of to differentially get rid of the seeds of invasives relative to the seeds of natives – by just waiting. Some seeds can last for decades while others (e.g., velvet grass) are very short-lived. If your invasive seeds are shorter-lived than your native, AND you can prevent invasive species from producing seeds in your grassland, then after a few years the number of invasive seeds in the seed bank will dwindle. So one thing you will want to know about your target species seeds (if available) is how long the seeds survive in the soil. All of the other techniques for reducing the number of seeds in the seed bank do not discriminate between invasives and natives.

- Flush Them Out – Flushing the seed bank by encouraging all of the seeds to germinate also has some potential for allowing natives to persist – although this could only be done on a small scale. Knowing that the seeds sprout, can sometimes be used to your advantage. For example, velvet grass (Holcus lanatus) often forms dense stands with a thick layer of thatch. If the adults are removed, the abundant seeds immediately sprout. One Achilles heel of this species may be that almost the entire seed bank will sprout if the adults are removed. This dramatic response provides an opportunity to remove the majority of seeds in the seed bank with a one-year treatment of the seedlings.

- Till Them All Under - if you are working with an area that has been tilled previously and has few or no native plants, it may be helpful to till. Seeds tilled into the soil are not able to germinate because they are too deep in the soil. However, tilling will also bring buried seeds to the surface where they will germinate. When restoring grasslands from scratch, Mark Stromberg has proposed tilling a field repeatedly so that no plants are allowed to set seed for 3 years. This allows restoration to begin “with a clean slate” as far as the seedbank is concerned.

- Cover Them Over – You can use a thick layer of mulch or black plastic sheeting to cover the suface of the soil. After prolongued coverage, many seeds will die under these conditions.

Adding seeds you do want:

- Adding native seeds to the soil has had varying levels of success. Many studies have shown little benefit. But some managers have had success if the seeds are added in areas conducive to seed germination, especially where other seeds are absent:

- Seeding into gopher mounds – Brock Dolman at the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center trains his folks to “huck and chuck” by stripping seeds off mature native grasses and throwing them into gopher mound dirt. The dirt from gophers often comes from areas deep in the soil without other seeds.

- Seeding into a medium grade wood chip mulch. Mulches of the right texture can provide a seed free substrate with enough moisture to encourage growth of native seeds while suppressing some of the existing seed bank.

Vegetative Growth

Rhizomatous vs non-rhizomatous? Vegetative growth is the growth of leaves and stems and roots (as opposed to reproductive growth of flowers, seeds, etc.)

Rhizomatous plants can grow horizontal stems, usually underground. Each node on the stem can send out roots and shoots. If a rhizome is separated into pieces, each piece can give rise to a new plant. This is a process known as vegetative reproduction and is used by farmers and gardeners to propagate certain plants.

Some invasive rhizomatous species have an amazing ability to grow from isolated, tiny fragments of the rhizome. This is problem that plagues land managers. You do your best to pull up all the roots of the plant, but unknowingly a ½ inch piece of rhizome was left in the soil. This tiny piece of rhizome sprouts and takes hold and in a short time you’re back to square one. Some species are particularly good at this, including velvet grass, Holcus lanatus and crab grass, Digitaria spp. Velvet grass can sprout from a seemingly dessicated rhizome lying in dry thatch, and tiny pieces of the rhizomes on crab grass break off when other roots are removed, fall to the ground unseen and later sprout and spread.

Rhizomatous species can be reduced using herbicides, tilling, hand pulling, mulching, and tarping:

- Herbicide use is not very desirable. It is expensive and even the most innocuous herbicides (i.e., Round Up) can have other side-effects in the ecosystem.

- Tilling is a one-way ticket to the destruction of any native species, including any micorrhizal associates. It also tends to break up the rhizomes which can actually enhance growth. Repeated and concerted efforts to till may be possible.

- Hand pulling or digging may be possible. Other non-chemical means are mulching and tarping.

Roots

Pesky perennials. If your invasive target species in an annual, you don’t have to worry about the root systems, since they will perish each year. But you do need to remember that if the roots of a perennial are alive, it will come back stronger than even next year. Perennials, both invasive and native, tend to have extensive root masses, especially if they are decades old.

If you have perennial invasives on your land and you decide to go after them, you are now working at the forefront of much of knowledge about how to deal with these new arrivals. Even as we write, managers are trying to figure ways to reduce invasive perennial grasses while maintaining native perennial grasses.

Any manager with a long-lived perennial invasive plant is going to have to take on the challenge of controlling and reducing root growth. As with rhizomes, there are only two effective ways to deal with roots: herbicides and tilling. However, there are some other techniques that are promising:

- Intensive rotational grazing and trampling may help with some species – had a negative effect on velvet grass at the Wick Ranch in Marin County. Possibly over time, it will lead to thinning of the non-native grasses.

- Pulling – However, some invasive perennials, such as Festuca arundinaceae, have roots that are strong enough to make pulling very dsloifficult. Others can be easier.

- Tarping or Mulching – a combination could work

5. Identify ways to reduce or enhance your chosen species.

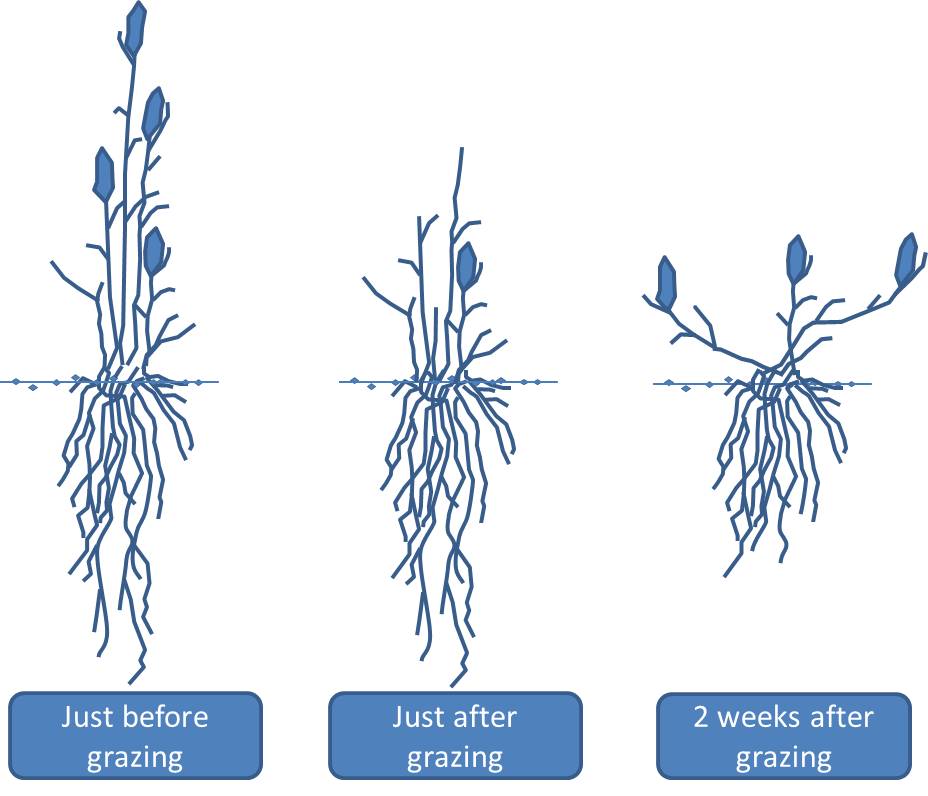

You now have some initial ideas about the strategies for developing a targeted management or restoration plan for your grasslands. We recommend using a visual approach to planning. The advantage of actually sitting down to diagrammatically show your treatment and what you anticipate is that both your assumptions and the need for monitoring the outcome become transparent.

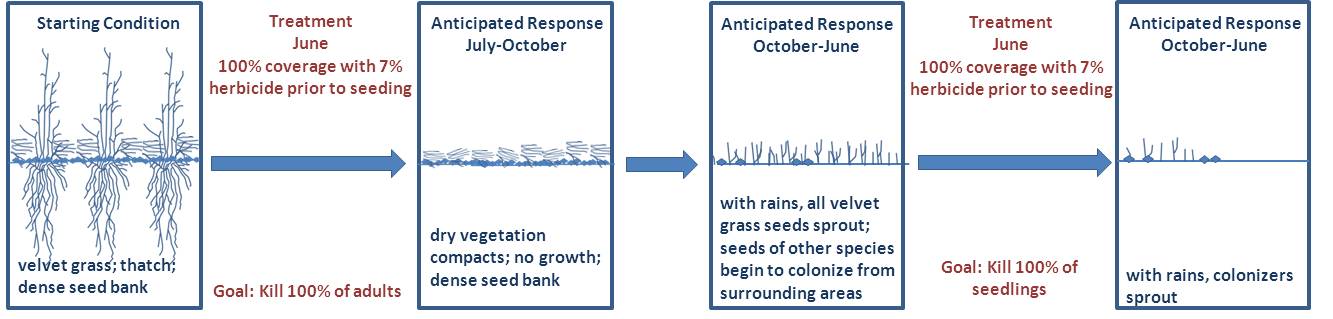

Here is an example of a diagram that one of used to design and monitor a effort to remove velvelt grass patches that were invading a native grasslands. Velvet grass occurred as isolated very dense productive patches and herbicide was prescribed on a small scale to eradicate this aggressive invasive.

In this example, you will notice a number of features:

- Predict How the Seeds, Leaves, and Roots May Respond - Four of the five key aspects of the life cycle of the grass (discussed above) are shown in the drawings: leaves and stems, roots, and seeds in the soil. (Seed heads are not shown because seeding was prevented during this particular treatment). By drawing these aspects of the species, it is hard to ignore them and mistakenly leave them out of your treatment protocol. We recommend considering how your treatment will have an effect on each of these plant parts. In the example above, herbicide will kill all the above and below ground parts, but will not affect the seeds.

- Specify the Treatment - The type, intensity, and timing of the treatment are described. As much as possible, remember to accurately describe your treatment. If for some reason your planned treatment fails (this happens all the time!), revise your diagrams to accurately reflect what occurred and then change your predictions based on your knowledge of the species involved.

- Measure Treatments, Goals and Anticipated Responses - Treatments, goals and anticipated responses should be assessed at each stage of the management process. Did you achieve 100% coverage? Did ALL of the seeds sprout during the first year after the adults were removed? Did natives colonize? While data collection to measure these reponses is ideal, few managers actually have the time and staffing to undertake the monitoring needed. However, it is easy enough to take a walk at your treatment site and take pictures and notes on your observations. If it is clear that your anticipated outcome is not achieved, it is better to revise your plan right away. Perhaps you need a second treatment before continuing.